Emu & Ostrich Farming

Did you know that around the world, emus and ostriches are farmed for their skin, feathers, flesh, eggs, and oil? These two incredible species are descendants from dinosaurs, and today, they are experiencing some of the most horrific treatment as their body’s are exploited for human use.

Emus and ostriches are known as ratites, a type of bird that has a flat breastbone without a keel and is unable to fly. Ostriches are only native to Africa [1], and sadly their population has been declining in the last 200 years. The main reasons for their decline are hunting, illegal predation on their eggs by humans, habitat destruction, climate change, and forage competition with other wildlife species [2]. Emus are only native to Australia [3]. Despite being on Australia’s coat of arms, limited research has been conducted on emus in their natural environment and little is known about the species.

Although you may not eat emu or ostrich, the industry impacts thousands of native animals each year, and unknowingly, their skin, feathers, and oil may be present in some of the products you purchase.

About Ratites

Like all animals, ratites are sentient beings capable of experiencing emotions like joy, happiness, fear, and pain. Although capable of defending themselves, ostriches and emus are still prey to many species, with the two most common being lions (to ostriches) and dingoes (to emus). Both have very primal responses to survive and use their fear instincts to sense predators. One difference is that ostriches are more aggressive towards people, while emus are more docile with a curious nature [4, 5].

Their bodies are incredible!

Ostriches

Despite being flightless, ostriches have wings which are used as rudders to help them change direction while running [6]! Their powerful legs enable them to reach speeds of over 65km an hour, and each stride is between 3-5m. They can comfortably outrun predators like lions, leopards, and hyenas!

Ostriches prefer warmer climates and their feathers are used to regulate their body temperature. Unlike other bird species, their feathers do get very wet, as they lack the uropygial gland [7]. While their natural habitat is the scorching hot desert, reaching temperatures of 48 degrees C, their bodies have the ability to stay around 18 degrees or less! If they get any hotter, their internal chemistry is disrupted [8].

Ostriches have acute eyesight and hearing so that they can sense predators from far away. Despite popular belief, they do not put their heads in the sand – they do, however, lay down on the ground to hide from predators. If they do come in contact with an attacker, they use their powerful leg muscles and sharp claws to deliver a strong kick, injuring and occasionally killing their attacker [9].

Ostrich running.

Emus

Emus are the only birds with calf muscles, allowing them to sprint or cover long distances. With their powerful legs, Emus can reach 50km per hour or 13.4m per second! While being shorter than an ostrich, their strides also average 3m. They have three forward-facing toes that help them grip the ground and also help them fight predators [10, 11].

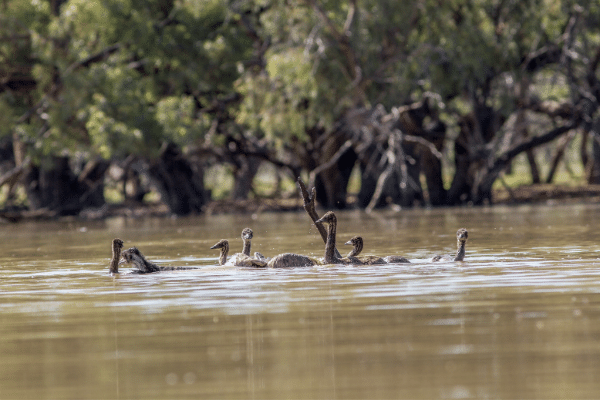

Emus can survive in hot, arid habitat because their grey and brown body feathers provide almost complete protection from solar radiation [12]. Surprisingly, they also love to swim [13].

Emu chicks swimming.

They have friends.

Ostriches

Ostriches live a nomadic life, roaming around the savanna, scrub, grasslands, and semi-deserts. Their flocks are typically made up of a dozen individuals, however, sometimes flocks mingle and congregate at water sources, and there can be over 100 individuals [14, 15 16]. Males are territorial and aggressive, particularly during breeding. They fight for 2-7 females, with whom they will mate. They exhibit cooperative breeding, where all females deposit their eggs into a communal nest. The alpha female will work with the male, taking turns sitting on the eggs. After 6 weeks, the chicks hatch – some broods can have up to 40 babies! The male is the primary carer, and the chicks immediately learn to follow him, clustering around his feet. He teaches them how to feed, and protects them from predators and the elements using his wings [17].

Father ostrich caring for young.

Emus

Emus typically live in pairs, however, they can be found travelling in mobs, most commonly when they are looking for a new food source [18]. Mating pairs will stay together for around 5 months. Some even enjoy living by themselves.

A female will aggressively fight for a single male and once paired, they form a tight bond for most of the year. Once the female lays the eggs she leaves to find a new mate, and the male incubates the eggs and raises the chicks. He will sit on the eggs for 56 days, eschewing all food and water. Once the chicks hatch, he teaches them what to eat, and protects them. They have been known to stay with each other for up to 2 years [19]! After this, they may wander in the same area for food, water, and a mate [20].

Emus wandering together.

They can live long lives!

If left to their own devices, ostriches can live to be 75 years old, however, the average age is 50 years old [21]. Emus typically live for 10-20 years.

About the industry

While not a huge industry, thousands of ostriches and emus are killed for their feathers, skin, flesh, eggs, and oil every year. For emus, the most “valuable” product is their oil [22]. The demand for these ratite products causes an immense amount of suffering, and the premature death, of these sentient beings. Australia, Canada, the US, Africa, and India, are some of the key countries involved in this industry. The demand for ostrich meat in Australia has remained relatively low, however, there is a strong international demand in the USA, Europe, and Asia [23]. Due to the small-scale of the industries, information is limited, and the below information on standard practices and welfare focuses on the Australian industry specifically.

Demand

Due to the small scale of the industries, slaughter statistics across the globe are difficult to find. In 2008, approximately 371,000 ostriches were killed around the world, while 5,344 emus were killed in Australia [24, 25].

Ostrich and emu skin is turned into leather and is used to create bags, wallets, and shoes. Their feathers are used by the fashion industry, for decorations, or for cleaning fine machinery or equipment [26]. Their flesh is sold as is, or turned into cold cuts, frankfurters, pâté, fillet steaks, and jerky [27]. Their eggs are predominately incubated and hatched to become the next generation of farmed ratites, however, some eggs are eaten or used in arts and crafts due to their large size. Emus also have a large reserve of fat on their backs. People discovered that this fat can be rendered to create an oil, and it is commonly used for “treatments” [28].

Example of an ostrich leather bag.

Welfare

Both the ostrich and emu animal welfare standards are full of recommendations, using the word “should”, rather than strict stipulations of minimum requirements [29, 30]. This means farmers are left to interpret the standards and do not have to follow them. On top of this, there is a range of welfare issues associated with farming ostriches and emus.

Breeder flocks

While ostriches and emus are given more room than other farmed species, such as pigs who are kept in sow stalls, they are still denied their natural nomadic lifestyle. There is limited information available regarding how long breeders are kept, however, emus are said to have a reproductive life of approximately 10 years, with “one or two breeding birds [being replaced] every few years” [31]. Ultimately, they would spend years moving between breeder pens and paddocks, before being forced onto trucks and transported to the slaughterhouse. Both species suffer from being denied the ability to roam the land and from socialising with others like they naturally would.

Ostriches

The ostriches used in Australia are a mix of African Black, Zimbabwe Blue, Kenyan Red, which have created the Australian Grey and unique Whites. Mixed breeding was done to exploit the desired qualities from the different species to maximise profits – i.e. the feathers of one, the fast-growing rates of another. Australia has less than 3,000 breeders (2009) [32]. The parent flock begin breeding at 3 years of age. In order to breed ostriches, they can be held in pairs or trios in well-fenced pens of just 25m x 60m [33], or run in paddocks as a small flock called a breeding colony [34].

Emus

When the domestication of emus began, some were taken from the wild and placed in captivity to breed. This is no longer legal to do [35]. Male and female pairs are kept in pens that should be a minimum of 400 square metres, to mate. In some areas where there is low vegetation and low rainfall, pairs should be given 2,500 square metres [36]. The pair will hatch between 20-30 chicks a year [37].

Grower Flocks

Ostrich and emu chicks can be raised in an intensive shed, or under semi-intensive conditions. In both cases, eggs are collected from breeding stock and placed inside incubators until they hatch. In the wild, chicks of both species would stay with their fathers for up to 2 years, learning survival skills. This industry completely strips the parents and chicks from their natural instincts and behaviours. For both ostriches and emus, the standards state that stocking density should change multiple times during their growth to provide more room to move – again, this is just a recommendation and is not enforced.

Ostriches

The standards state that ostrich chicks “should” be given access to an outside run, where they have a minimum space allowance of 1.5 chicks per square metre. Inside the sheds, the space recommendation is 3 chicks per square metre. For mature ostriches, it is recommended that there is a maximum of 12 birds per hectare of dry land or 24 for high rainfall/irrigated land [38].

Sick or injured ostrich chicks can be killed by cervical dislocation or decapitation, however, older individuals can be killed by a gunshot to the head [39].

Outdoor ostrich paddock.

Credit: Justin Mcmanus

Emus

Some farmers do allow the male emus to incubate the eggs, however, once hatched, the chicks are placed inside sheds to grow [40]. Emu chicks are farmed indoors and outdoors, or a combination of both, known as “semi-intensive” conditions. While emus must be provided with more room than other factory-farmed animals, they are still living unnatural conditions. The standards say that chicks should be placed inside heated sheds, and after three days are allowed access to an outdoor run. When they are 12 weeks of age, they are moved into a paddock and do not return to the brooding shed.

On farms, emus have a mortality rate of 7-12% up to 3 months of age [41]. One of the biggest issues is that they can be housed with up to 400 others – a drastic difference to living with just the father and siblings, and then in pairs.

For emus aged 6 months to 18 months old, the standards state that on lush or irrigated land, there should be a maximum density of 175 birds per hectare, or for more bare conditions, 100 birds per hectare. On a “free-range” farm, this reduces to 18 per hectare of dry land or 24 per hectare of irrigated conditions [42].

Toe-trimming

Toe-trimming is a common management tool used to “improve skin quality and worker safety and reduce birds stress” [44]. Both ostriches and emus may scratch others when walking around, trying to get food and water, or during fights caused by the unnatural crowded living conditions. As a result, they develop scars which reduce their “grade” and ultimately, farmers’ profits. As a way to combat this issue, instead of reducing the stocking densities and providing the animals with a more natural environment, the industry conducts toe-trimming.

When chicks are one day old, a worker uses a heated blade to amputate part of each toe and nail to prevent the nail from growing back [45]. Alternatively, they can use “sharp clean shears, a beak trimming machine, or other suitable device, angled to retain the bottom part of the last phalanx within foot pad” [46]. There is no legal requirement to give emus or ostriches anaesthetic or pain relief.

Diagram of toe trimming for emus and ostriches.

Toe-trimming has proven to cause both acute and chronic pain resulting from tissue and nerve damage and may result in behavioural changes. Severing the toe means nerves are also severed and can cause pain and discomfort in the ratites. They also heal abnormally, which can cause them to be sensitive to temperatures, or touch. Some develop traumatic neuromas or will experience phantom limb [47, 48]. Ratites walk on their toes - decreasing the number of toes forces them to change the way they walk and can lead to mechanical stress exerted on the toes. Despite this, there has been no research on the impacts toe-trimming has on gait [49]. In saying this, one paper did state that ostriches are known to slip around on wet ground after toe-trimming. In Australia, most emu and ostrich farms conduct toe-trimming [50].

Chick with toes trimmed. *Not Australian

Credit: African Geographic

Health issues

Keeping any animal in unnatural and/or intensive conditions can result in disease outbreaks and illness. Both ostriches and emus can suffer from the build-up of ammonia in the sheds. Farm-captive emus are known to suffer from coughing, panting, lameness, and swellings on the body or legs [51]. Ostriches commonly suffer from leg rotation and bruising from handling and other trauma, which can cause lameness. If they have difficulty standing, walking, or have heat, pain, and swelling, they must be “destroyed” [52].

Live-plucking

Thankfully, the live-plucking of ostriches is unacceptable in Australia, however, the white wing feathers and darker bottom feathers can be removed by cutting above the bloodline. The reason this is done before they are slaughtered is to “prevent contamination of the quality feathers during slaughtering and processing stages”. All other feathers are removed after slaughter [53] In other countries, however, live-plucking does occur.

The emu standards, however, have no mention of live-plucking.

Two ostriches that have been plucked while still alive.

Credit: UPC *Not Australia

Transport

Transportation is incredibly stressful for the emus and ostriches. While the Australian standards say that transport should be kept as short as possible, the lack of slaughter facilities prevent this from happening, with many having to travel interstate [54, 55]. Both species are transported in fully enclosed, dimly lit vehicles, in an attempt to reduce their stress, and also to prevent the public from seeing them. Adult emus and ostriches can be on transport trucks for 36 hours, and 24 hours for juveniles [56]. The stocking density of trucks varies for the different weights.

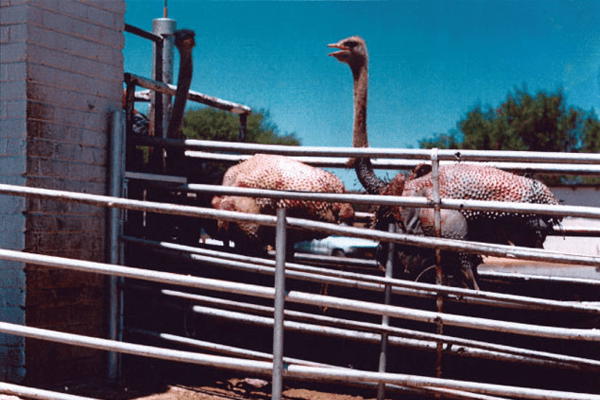

Ostriches

It is recommended to push ostriches into a ‘V’ shaped crush, to make it easier to restrain them. Alternatively, a shepherd’s type hook can be used to restrain the head, making it easier for the worker to put a hood over their head – known as “hooding” [57]. In the Ostrich welfare standards, it states “the crate height should be at least equal or greater than the head height of the birds being transported; and no more than 10 birds in a compartment”, however, it doesn’t give specific dimensions for the compartment [58].

Credit: MSD Manual & San Diego Reader

Emus

Emus cannot be herded, so workers have to coax them into the trucks with feed or by appealing to their natural curiosity [59].

For emus, it is suggested that there be 8 birds per meter squared for birds less than 7kg live-weight; 3 birds per meter squared for birds weighing 25-30kg, and 2 birds per meter squared for mature birds 35-45kg live-weight [60]. Emu chicks aged 7-14 days old are also being air freighted around Australia for domestic buyers to start their own flocks [61]. These chicks would naturally rely heavily on their father to teach them life skills, and the removal and transportation experience can be very stressful for them.

Export

Some companies export eggs and day-old chicks all over the world, sending them to New Zealand, Vietnam, Pakistan, Spain, Greece, Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Nepal, Malaysia and many other countries [43]. Australian companies also send them domestically.

Slaughter

All ostriches and emus must be electrically stunned or made unconscious by a captive bolt gun before being bled out [62]. There is no Australian footage of ostriches and emus being killed in Australia.

Ostriches

Ostriches are killed at 9-12 months old, cutting their lives short by over 49 years [63]. PETA US exposed the killing of ostriches at the world’s largest ostrich slaughterhouse in South Africa in 2015.

Emus

Due to the lack of slaughter facilities in Australia for ratites, emus are being killed on-site. As these farms are not approved slaughterhouses, their flesh cannot be used for human consumption - making their lifeless bodies “waste”. The farmers instead profit off their skin, feathers, and oil. This leaves the emus vulnerable to being killed in improper ways. Emus are killed at around 12-18 months of age, although some farmers keep them for 24-30 months [64], dramatically shorter than their natural lifespan of up to 20+ years.

Environmental impacts

Due to the size of the industry, environmental impacts have not been assessed on a global scale. This section will focus on the importance of emus in Australia, and the impacts of ostrich and emu farms in terms of land clearing and waste production.

Why we need Emus

Emus play a pivotal role in the Australian ecosystem. They help native species regenerate, as they disperse a large quantity of seeds over large distances, and could aid remnant vegetation by maintaining the necessary mix of different plant species in an environment. One emu scat can contain 1000 seeds, and these animals can travel over 50km [65, 66].

Threats to Emus

In just 100 years after colonists invaded Australia, emu varieties in Tasmania, King Island, and Kangaroo Island were driven to extinction. Coastal populations on the north coast are in rapid decline, with less than 50 birds left in 2016 [67, 68]. Current threats to emus include native vegetation clearing for both agricultural land and development, as their homes are destroyed and there are more barriers affecting their movements, an increase in vehicle accidents, and predation from species such as dingoes, eagles, snakes and other nest raiders [69].

Land Use

As outlined above, chicks and breeders may be given more room than other species who are farmed. While this is better for the animals, it is more taxing on the environment as additional land has to be cleared or fenced off to support the farm. Land clearing and removing natural habitat is responsible for a dramatic loss in natural biodiversity [70]. On top of this, the land must be cleared to grow their feed. Australian species have suffered an extraordinary rate of extinction over the last 200 years for this very reason [71]. A 2018 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America found that 60% of all mammals today are livestock (cows, pigs, sheep, goats, horses etc.), and just 4% are wild mammals. Additionally, of all the birds on Earth, 70% are farmed poultry – meaning just 30% are wild [72]. Due to the value of emus in Australia’s ecosystem, it is a damaging move to section off the land for farms, threatening wild populations.

Cleared land for an emu farm in Kerang.

Credit: The Land

Emissions and Waste

Ostrich and emu farms are a producer of emissions and waste. Inside the sheds, waste can accumulate, which produces water vapour, heat, ammonia, hydrogen sulphide, carbon dioxide, and dust particles. [73]. An international analysis of ostrich farming found that ostrich farms produced more pollutants than chicken farms. Ostrich farms produced 5 times more CH4, 10 times more N2O, 6.8 times more NH3, and 6.5 times H2S than those of the chicken production system [74].

The farms typically deal with waste material made up of litter, dead birds, reject eggs, shells, dropped food, and excretions. This is discarded in a farm pit or burnt. Offal from slaughterhouses is sold for fertiliser [75]. Using animal waste as fertiliser can also pollute waterways, disturbing the water quality, while also upsetting the natural nutrient balance in the area [76]. On farms that kill emus, their flesh is discarded as “waste” and the fat is kept for oil [77].

Health impacts

Red meat

Both ostrich and emu flesh is classified as red meat, meaning that there is a probable chance that it can cause some types of cancer [78]. While the Cancer Council says you can eat it in moderation (a few times a month), more doctors are coming out saying that the healthiest diet is a whole-foods, plant-based one [79]. While red meat does contain protein, iron, and other essential nutrients, so do a variety of plants (without the nasties).

Vaccinations, antibiotics, and antibiotic-resistant diseases

Studies have found that ratites should not be farmed near other birds, from waterfowl to poultry, due to their susceptibility to disease and illnesses [80]. To reduce the chance of outbreaks, farmers can add antibiotics to their feed [81, 82], and vaccinate them. Emus are vaccinated against Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, and ostrich chicks are given a clostridial vaccination [83 doc]. The standards for emus and ostriches state that “where it is proposed to slaughter ostriches/emus that have received medication, advice should be sought from professionals of relevant government agencies to ensure that there is no residue in the meat” – meaning it is not mandatory and consumers could be ingesting the medication second-hand.

In Victoria, an emu farm in Kerang killed at least 3,000 adult emus and 2,000 chicks after an outbreak of avian flu [84]. With the current Coronavirus pandemic, we should be working together to change our food system to reduce the chances of any future pandemics.

What’s Next?

Most people are unaware of the plight of farmed ostriches and emus around the world, and more specifically, in Australia. Share this information plays an important role in generating awareness, and working towards ending the suffering of these animals. You can make a difference by making the decision to never purchase emu or ostrich meat, leather, feathers, or oil. To help further, learn about animal-free alternatives, and support Animal Liberation’s efforts to make a more compassionate world for animals -