Dairy Farming

When we think of dairy milk, we often think only of the milk produced by cows. Although less common, there are plenty of other species involved in dairy production - goat, yak, camel, sheep, zebu, and even reindeer, horse, and donkey are all types of dairy milk consumed around the world. Interestingly, we have become so accustomed to drinking dairy that little thought goes into why the milk from some animals has been normalised, and the thought of drinking milk from other animals may make us a little uncomfortable.

Let’s explore some facts about the mammals used in the dairy industry, the way the industry operates, the environmental impacts of our demand for animal milks, and the impact it has on our health.

Milking a horse.

Credit: Michael Turtle

The Animals

Mammals only produce milk for their young

Just like humans, cows, camels, goats, yaks, buffalo, horses, donkeys, sheep, reindeer, and zebu, produce milk for the purpose of nourishing their babies. All mammals have mammary glands, and pregnancy stimulates the progesterone and oestrogen hormones, which promote the development of the milk duct system in their bodies [1].

All of these animals carry their young inside them for months, forming a connection with them. Sheep and goats have pregnancies of approximately 5 months [2], yaks 8 months [3], cows 9 months [4], buffalo and zebu 10 months [5], horse 11-12 months [6], donkeys 11-14 months [7], and camels 12-14 months [8].

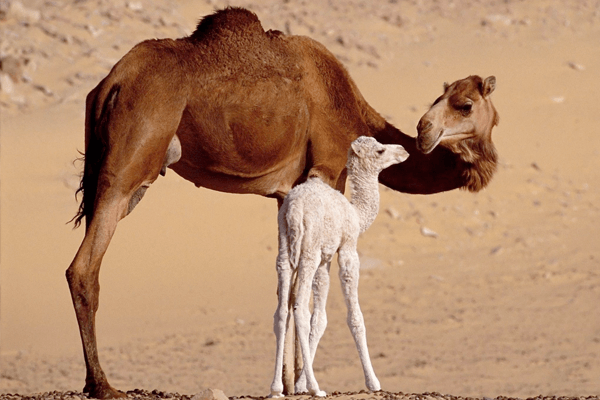

Mother camel with her calf.

Mammals are maternal

Mammals care for their young into adulthood, to ensure their infant survives and will eventually reproduce [9]. Mothers across all species are known to nourish their young, defend and protect them, and teach them how to survive. The dairy industry purposefully denies mothers of a chance to bond with their young, as the babies are seen as competing for the resource – being the milk [10]. Both mothers and babies suffer from the separation.

Focusing on cows, as they produce 85% of the world’s animal milk supply, a cow would nurse her calf for approximately 7-14 months [11]. In as little as 5 minutes postpartum, mother and calf develop a strong specific maternal bond [12]. Being a herd animal, cows and their young would typically stay together for future generations. Bulls, however, may leave to start their own herd. After separation, cows are known to look for their calves and bellow out for them, while calves also become more vocal. A more recent study found that calves who are removed from their mothers are less social and active [13].

“Calves hate being weaned and cows hate their calves being taken away, whether after one day or five months. But it is better to do it before a bond has developed. In nature cows would live together as a family with cows and their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, so we are already interfering a lot with that family process.”

Helen Browning, Dairy Farmer [14].

The Industry

There are millions of animals of various species trapped in the dairy cycle. If we look at just cows alone, there are over 270 million spread around the world [15].

While not common in Australia, cows may be kept indoors for all or part of the day. Many large-scale dairy farms around the world keep the cows in sheds, with no access to pasture for their entire lives. This increases locomotive disorders, lameness, mastitis, boredom, and stereotypies (abnormal behaviours such as tongue rolling) [16]. Dairy products that are imported may be supporting these farms.

Australian Standards & Welfare Issues

Australia has around 1,562,000 dairy cows, spread across 5,700 farms. These mothers produce 9.3 billion litres of milk every year [17]. The average Australian drinks 107 litres of milk, eats 14 kg of cheese, and 4kg of butter in a year [18]. On top of this, there are 68 goat dairies, producing 16 million litres per year [19], 5,500 sheep across 13 sheep dairies, producing 550,000 litres [20], and approximately 8 camel dairies, producing around 50,000 litres a year [21].

The following standards are common across the globe and are used on multiple species, but predominantly cows. The sources used are relevant to Australia.

Milking

Credit: Animals Uncovered

Artificial Insemination

Artificial insemination (AI) involves placing semen directly into the uterus, rather than allowing animals to naturally mate. Using AI means farmers do not have to care for males, and they can access semen from males all over the world, having more control over genetics, and can impregnate more females in one season [22].

The female is usually restrained, often inside a crush box. A worker inserts their arm into a cow’s anus and then with the other hand inserts a semen straw into her vulva. Using the hand that is already inside her, they guide the semen straw into her uterus and release the contents [23].

Semen Collection

In order to use AI, semen must be collected. There are a few methods, but all involve exciting the animal, either with a female, fake female, or mounting device, and collecting the semen inside an ‘artificial vagina’ that has a vial attachment on the end [24, 25].

For bulls, some farmers use electro-stimulation, where an electric rectal probe is inserted into the bull’s anus, forcing them to ejaculate [26]. This method is regarded as painful, causing physical pain, stress, and anxiety [26].

Separation and killing of babies

Most babies are separated from their mums after birth, as they are seen as competitors for the milk. Allowing the calves to consume the milk will reduce the supply for humans. As mentioned previously, this is extremely traumatic and distressing for both mothers and babies. It is simply not economically viable to keep all offspring alive, for this reason, many are killed after birth.

Cows

In Australia, calves are usually taken from their mothers within 12-24 hours after birth, and both show a strong emotive response to the separation, though it is stronger if the calf is taken at an older age [27]. Cows are known to chase down the vehicles with their calves and bellow in distress.

“A dairy farm worker explained that the cows remember which vehicle came and took their baby away shortly after birth. On subsequent occasions when farm vehicles would drive past they would behave no different, no different that is until the one vehicle that took their baby would return. At this point, the cow would become nervous, anxious and edgy, looking for the baby she would never see again.”

Edgar’s Mission [28]

In 2017, Animal Liberation released world-first footage of dairy calves being taken from their mothers [29]. In 2020, a backpacker captured footage from her time on an Australian dairy farm, which showed mothers chasing the trailers with their babies.

To the dairy industry, ‘bobby calves’ are newborn calves without their mothers, and are considered a surplus to the industry as they are not required for the dairy herd. While roughly three-quarters of females are kept to replace ‘spent’ dairy cows, and both sexes may be used for veal or beef production, many are killed straight after birth on the farm, or within a week of life at a slaughterhouse. Every year roughly 500,000 bobby calves are slaughtered in Australia [30].

Whether a calf is killed immediately, or kept on a farm and raised for veal or beef, both scenarios lead to the same end - one is just prolonged. In Australia, between June 2019 and June 2020, 564,000 calves were killed for veal [31].

In 2019, Animal Liberation exposed the sale and slaughter of bobby calves in Australia:

Goats

Kids are removed from their mothers within hours of birth. A study found that goats can remember their babies call after being separated for a year [33]. As with calves, female kids may be kept to replace ‘spent’ dairy goats and few males are kept for breeding. Others may be grown out for meat, however, there is always a surplus resulting in many being killed onsite [32]. On a goat dairy, there is typically one male (buck) per 30-40 females (does).

In 2019, Animal Liberation Victoria exposed the legal killing of kids (baby goats) on an Australian Goat Dairy farm. Footage showed kids, who were less than 24 hours old, being bludgeoned to death with a metal pipe [34].

Camels

The camel dairy industry is fairly small in Australia. This industry operates a little differently to cows and goats, as camels produce more milk when with their calf. Some dairies allow the baby to drink from one teat, while the other is hooked up to a milking machine. Once the baby is weaned, the mother stops lactating and remains with the herd until she is impregnated again.

As with cows and goats, some of the young females become a part of the dairy cycle, while the males are slaughtered for meat or may be sold to another exploitative industry, such as racing and rides.

Melanie Faith Dove

Dehorning and Disbudding

Most breeds of dairy cows and goats develop horns as they grow. Horns are considered dangerous to workers, and for this reason, both calves and kids are disbudded or dehorned in Australia and around the world [35]. The industry also claims it is to protect the animals from injuring each other, however, this is due to the unnatural living conditions, boredom, frustration, and changes to the herd.

Disbudding

Disbudding is the removal of the horn buds before they form an attachment to the skull. Disbudding involves using a hot iron to cauterise the developing horn bud, preventing further growth [36, 37]. This is typically performed on calves that are 6-8 weeks old, and goats who are 3-7 days old. A veterinarian can give local anesthetic, sedation, or anti-inflammatories, however, if a vet does not perform the procedure, animals can have this done without pain relief and then be given a topical anesthetic after the procedure [38].

Dehorning is more invasive as it requires removing the horn after it has connected to the skull. This is usually performed with a ‘dehorner’ or knife [39].

Tail docking

In most Australian states, it is legal to dock a calf’s tail [40], with approximately 4% of dairy farmers performing it [41]. This is done using a rubber ring, sharp knife, or hot docking iron, and is done without pain relief. It causes chronic pain, inflammation, and lesions. It also reduces the cow’s ability to swat flies away, which can cause irritation and annoyance [40].

Inability to express natural behaviours

Insufficient space, changes to herd structures, removal of babies, separation, and lack of stimulation, can cause immense suffering to animals in the dairy cycle [35].

Unnatural milk production

Cows descend from the Wild Ox and have been genetically altered through selective breeding to increase desired traits, like milk production. Up until the 1800s, the average milk yield of a cow was around 1,000 llitres per year, enough to sustain and grow her calf into adulthood. By the 1950s, dairy cows in most countries were producing around 3,000 litres per year, and now in the 2000s, cows can produce up to 10,000 litres every year [45 PDF, 46]. In Australia, cows average around 6,169 litres [47].

Credit: Animals Uncovered

Mastitis

Mastitis is an inflammation of the udders due to an infection, caused by bacteria or injury (caused by the milking machine). According to the RSPCA, 5-10% of dairy cows suffer from this in Australia. Cows with mastitis show visible signs of discomfort, such as abnormal posture, increased sensitivity to the udders and teats, rapid breathing and heart rate, and high temperatures. This condition can be difficult to detect in the early stages, leaving cows in pain. If left untreated it can cause death [48].

Lameness

Welfare issues, such as lameness and hock injuries affect one-quarter to one-half of cows on dairy farms on average [49].

Lameness is when cows have pain in their leg or hoof, that affects the way they walk and their ability to put pressure on it. It can be caused by an injury or a disease. It can be caused by living on wet surfaces, standing on concrete floors for long periods of time [50,51].

The hoof of a cow with painful ulcer which causes lameness.

Credit: Dairy Australia

Trapping Camels

Camels are being caught in the wild and transported to camel dairies. The catching, handling, and transport of camels is incredibly stressful for the individuals, as they have been wild for many generations. The close contact with humans can cause acute lameness, damage to tendons, ligaments, and bones, bruising, fighting due to mixing groups, infections, feeding disruptions, and abortions in pregnant females [52]. While this industry claims they are providing homes or ‘sanctuary’ for the camels, the industry subjects these animals to mother and baby separations, repeated pregnancies, and eventual slaughter when milk production slows. Often the males (bulls) are sent to slaughter, as they are not economically viable to keep.

Wild camels trapped.

Credit: ABC

Slaughter

The ability of all mammals to reproduce and produce milk slows down at a certain age. As a result, the industry calls these females ‘spent’ as they are no longer economically viable to keep, and sends them to slaughter.

Cows

While cows can live for 20+ years, the typical dairy cow will be sent to slaughter at just 7 years old, often while they are pregnant. Some individuals break down by the age of 3, and few last until they are 10 [43].

Alternatively, they may be sent overseas on live export ships.

Goats

Goats can live for 15-20 years but are killed when they are no longer producing an ample amount of milk. Farmers may kill them onsite, send them to slaughter, or export them overseas [44].

The Environment

This section focuses on cow dairies, as they are the most common in Australia, and cow dairy is the most consumed around the world. Studies have concluded that dairy production, including cow milk and cheese, is significantly implicated in increasing “the environmental burden” posed by animal production [53].

Land Use

Almost 80% of the world’s agricultural land is used for farming animals. According to the ABS, in Australia, 4 million hectares of land is owned by dairy businesses and is used for grazing [54]. According to a global study, just one kilogram of milk requires roughly 8.95m2 of land, while cheese requires 87.79m2 [55]! If we continue with our current diet which is high in animal proteins and by-products, studies have found that close to 100% of land projected as required to feed the world on current diets “would be the result of increased dairy consumption” [56].

Not only does clearing native habitats contribute to a loss of biodiversity, but it also destroys the soil structure, increases wind and water erosion (leading to more pollution), and affects the ability of the soil to absorb carbon [57, 58].

Land clearing for farms and feed.

Resources

The dairy industry is a major user of water across the globe. In Australia, the industry accounts for 10% of water use [59]. According to the Save Water website, top operators use 500 litres of freshwater to produce 1 litre of cow milk [60], while the average remains between 628 and 800 litres [61]. One kilogram of cow cheese, on the other hand, requires 5,605 litres of water [62]! With a growing global population, water scarcity is becoming even more of an issue. Water Management Institute’s assessment projects that by 2023, 33% of the world’s population will be living in areas of absolute water scarcity [63].

In Australia alone, over 4,650,000,000,000* litres of freshwater is used to produce just 9.3 billion litres of milk annually.

*This figure is based on the top operator use of 500 litres of freshwater per 1 litre of cow milk.

Cows also require feed. In 2018–19 the national average was around 1.6 tonnes of feed per cow per year, unchanged from the last two years [64]. It would be more efficient to use this food for people instead of feeding animals who are going to be slaughtered.

Waste and Pollution

Cows are known methane producers. For one kilogram of milk, 3 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions are produced, most of which is methane. Cheese, on the other hand, produces 21 kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram [65, 66]! In Australia, the dairy industry is responsible for 12% of all greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture industry [67].

A dairy cow typically produces 52 kilograms of manure each day and around 21 tons per annum [68]. 2,500 dairy cows produce as much waste as a town of 411,000 humans [69]. Cows require nitrogen and phosphorus in their feed. To increase “reproductive efficiency”, they are fed higher levels, however, the unabsorbed nutrients are excreted through their fecal matter. A lactating cow excretes 63-81% of the nitrogen it consumes [70, 71]. The nitrogen and phosphorus have the potential to cause environmental pollution to both soil health and water [72]. The dairy industry as a prime contributor to water pollution, particularly eutrophication.

Health Impacts

Debate surrounding the consumption of dairy and associated health risks has been ongoing. Despite the industry claiming dairy is a health food, numerous studies show this to be untrue.

Lactose Intolerance

Humans are the only species to consume milk after weaning into adulthood, and are also the only ones to drink milk from another species. The purpose of milk is to help a newborn grow and develop into adulthood. Approximately 65% of adults around the world have lactose intolerance [73]. As an infant, our bodies naturally produce a digestive enzyme called lactase, which breaks down lactose from our mother’s milk. As we grow, and no longer need milk, our body stops producing this enzyme [74]. Therefore, it is unsurprising that over half of the human population struggle to digest the milk of other species into our adulthood.

Kids (baby goats) drinking their mother’s milk.

Osteoporosis

Milk is often promoted as essential for strong and healthy bones, however, studies have found the opposite. A Harvard study found that milk consumption during teenage years was not associated with a lower risk of hip fractures in older adults. Further, it found a 9% increase in risk for men who drank an additional glass of milk per day during their teenage years [75]. This could be due to the D-galactose found in milk, which has been shown to increase ageing in lab animals, shortening their life span, causing chronic inflammation, a decreased immune response, and gene transcriptional changes [75].

“The countries with the highest rates of osteoporosis are the ones where people drink the most milk and have the most calcium in their diets. The connection between calcium consumption and bone health is actually very weak, and the connection between dairy consumption and bone health is almost non-existent.”

Amy Lanou Ph.D., nutrition director for the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine in Washington, D.C.

Cancer

Another study found that high intakes of dairy products, such as milk, low-fat milk, cheese, and dairy calcium sources (but not supplemental non-dairy calcium), may increase one’s risk of prostate cancer. The results for the different types of dairy products and sources of calcium suggest that other components of dairy, rather than fat and calcium, may increase prostate cancer risk [76]. The consumption of dairy can increase the risk of lung cancer, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer [77].

Cow milk is meant for calves.

Other Links

Other possible health ramifications of cow milk consumption and dairy products include a modest increase in the risk of Parkinson’s disease [78], increased risk of type 1 diabetes development [79], cardiovascular disease, and increased mortality rates [80], as well as a strong correlation between cow milk consumption and the incidence of multiple sclerosis. Cow milk is also a top source of saturated fat, which contributes to heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease [81].

Plant-based Calcium Sources

What’s next?

We hope you have learnt something new about the animals, industry, and impacts associated with dairy farming, and dairy consumption. With so many alternatives available, thankfully we no longer need to support the cruel dairy cycle, and can consume nutritious and delicious dairy-free replacements. If you’d like to start reducing your dairy intake, take the pledge to drop dairy today and receive a free e-book with alternatives