All About Lamb

About sheep

Sheep, like dogs, can learn their name and be trained to perform tricks. Even more impressive, a study tested the ability of sheep to learn associations between stimuli, actions, outcomes, and adapting behaviours. It found that sheep can perform ‘executive’ cognitive tasks, something that is an important part of primate behaviour and has never been shown before in any other large animal [1]. Sheep can also differentiate between facial expressions, preferring a smile to a frown [2].

Sheep have complex social structures and develop long-term friendships, sometimes with other species. The concepts of loyalty and friendship are driven by emotions. In 2009, a study found that sheep can experience the emotions of fear, anger, despair, boredom, and happiness [3]. A study in 1993 found that rams would look out for one another, intervening on behalf of weaker sheep, support each other in fights [4], and even grieve when one dies or is gone.

The industry

Farmers often use the sheep for both their wool and flesh, meaning the meat and wool industries are inherently connected. To maximise profits, the sheep are most commonly cross-breeds or dual-purpose breeds (border Leicester, Corriedale), or Suffolk (just meat). Lambs are often sheared just before slaughter, at around 8 months old, despite having a life expectancy of 10-12 years. Some have been reported to live for over 20 years [5].

The global sheep meat market stands at over 1 billion sheep [6, 7]. Each year approximately 550,000,000 of them are killed for human consumption [8]. Australia has a flock of around 63,700,000 (down from 72.1 million in 2018 due to drought) [9], and kills around 21,000,000 lambs annually [10]. An additional 8,400,000 sheep are killed when they are deemed unprofitable by the wool industry due to slowing reproduction and brittle wool at around 5-6 years old.

In Australia, standard farming practices include tail docking without pain relief if they are under 6 months old [11], castration without pain relief using rubber rings to cut off circulation or a lamb marking knife [12], and mulesing (cutting the flaps of skin and muscle from a lamb’s breech) with a hot blade or sharp knife, also without pain relief [13]. Lambs are often tails docked, castrated, and mulesed at the same time. A lamb can be killed by a blow to the forehead if they are under 10kg when there is no firearm, captive bolt, or lethal injection available [14], and sheep can be killed by being bled out if there is no firearm, captive bolt, or lethal injection available [14].

Farmers in Australia practice winter lambing to breed the highest number of lambs at the lowest cost and to meet consumer demands and maximise profits. This means sheep are impregnated so that they give birth in the winter months, and their lambs are weaned during spring when pastures are most fertile. Triplet breeding (due to selective breeding), combined with winter lambing, increase the chance of lamb mortality due to the mother's inability to care for all three young, and their lower body weight making them more susceptible to the cold [15].

As a result, an estimated 1 in 4 lambs die from exposure and malnutrition within 48 hours of birth - that’s approximately 15 million lambs a year [16]. On farms where selective breeding isn't practiced, and a ewe only gives birth to one lamb at a time, the mortality rate is closer to 1 in 5 in colder areas and 1 in 6 in warmer climates.

In Australia, mutton (the meat of full-grown sheep) is not very popular. As a result, the industry sends live sheep onto ships to be slaughtered overseas. In 2019, over 1,100,000 sheep were sent on live export ships [17]. Live export causes intense suffering before and during the export journey, and on arriving at the destination for slaughter [18]. In 2018, a whistle-blower filmed the conditions on live export ships. Sheep, with almost no room to move, were suffering from heat stress due to poor ventilation and were unable to reach their food and water. They were stuck in mounds of wet faeces, blinded from infectious disease, and lambs were being killed onboard [19, 20].

The environment

To make room for approximately 63.7 million sheep in Australia [21], land is continuously being cleared. In 2017, Australia was placed in the top 10 land clearing nations in the world [22]. Clearing native vegetation threatens biodiversity, impairs the functioning of terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems, and is a key contributor to human-induced climate change [23].

The sheepmeat and wool industry are directly related to the destruction of dingoes, both native Australian animals, as they prey on the lambs and are considered a “pest” to farming; and kangaroos, as they "compete" for resources [24, 25].

Our health

Lamb, being red meat, is known to increase the risk of heart disease, cancer, a stroke, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and a heart attack. Doctors around the world are encouraging people to reduce their meat and dairy intakes, replacing them with whole-foods, like legumes, grains, nuts, fruits and vegetables [26]. Studies have found a link between TMAO (a chemical derived in part from nutrients abundant in red meat) and the increased risk of heart attacks and strokes [27, 28]. Other research has found that the heme-iron content in red meat could be accountable for the increased risk of diabetes [29]. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC, classified the consumption of red meat as probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A), based on limited evidence that consumption of red meat causes cancer in humans and strong mechanistic evidence supporting a carcinogenic effect. It was mainly observed for colorectal cancer, but also found associations with pancreatic and prostate cancer [30 PDF].

Vegan “Lamb” Recipes

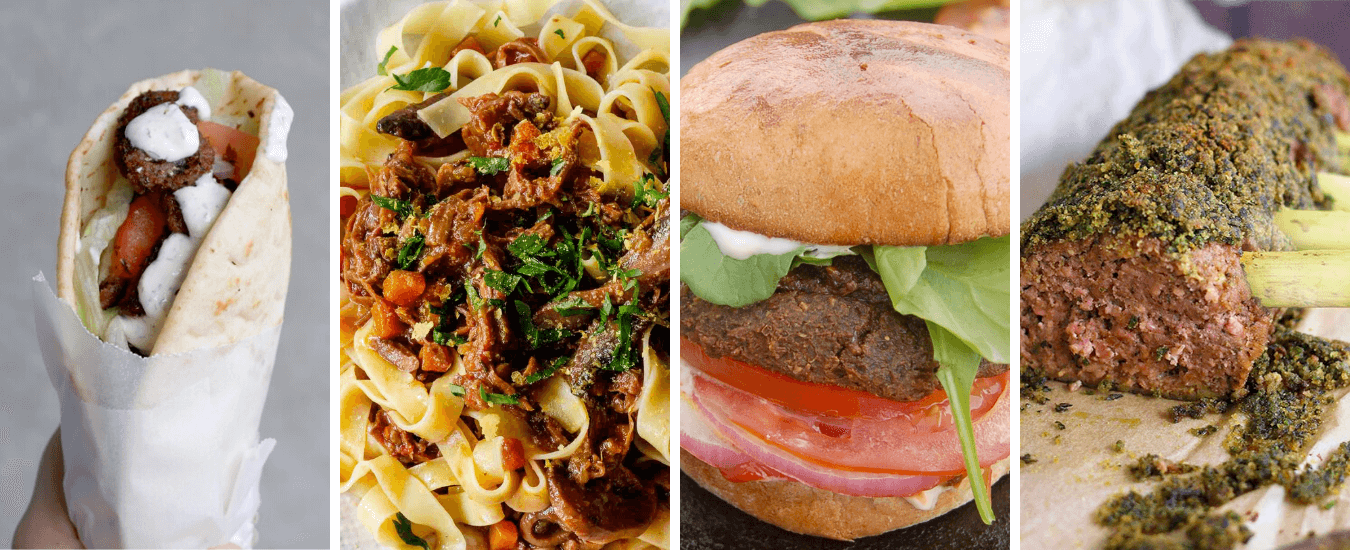

We hope last week’s vegan “beef” recipes helped you see that veganism isn’t about eating “grass” or tasteless meals.

The vegan mock meat game is growing, but currently lacks a wide range of vegan “lamb” alternatives. Although there are a few around, they might be a little bit harder to find. You can buy Ayer’s Vege Lamb online or check out your local Asian grocer for some other options. If you’re in NSW, order some of I Should Be Souvlaki’s delicious “lamb” protein, “lamb” pizza, and “lamb” stew; and if you’re living around Bondi, head over to Vegan Lebanese Street Food for their mouthwatering “lamb” shawarma (deliver to select areas too).

If you’re unable to find a mock meat replacement, you might have to step a little more out of our comfort zone, by replacing the lamb with more wholesome ingredients, like textured vegetable protein, legumes, and vegetables. One of our tips is to use the exact same recipes as before, but replace the meat with some beans or TVP. This way you have the same enjoyable flavours, without hurting any animals!

Here are some of our top vegan “lamb” recipes:

Pasta

Casseroles

Stew

Roast

If you have a little extra time, you can try making your own vegan “lamb” with one of these awesome recipes:

Meet Jason

Jason, our six-year-old, came five years ago from a shelter in Western Sydney. He’d been found in a rocky, swampy, otherwise-empty lot, lost or abandoned, we’ll never know which, and needed to be quarantined and his rotting feet carefully tended.

Three weeks in his own nook under the southern side of the house, with a small yard to graze in, and we were able to release him into the paddock with our other three. When the time came to find him another home, we couldn’t let him go. It’s probably a consequence of his swampy beginnings that he loves drizzly days. He’ll take cover when it’s heavy, but light rain is his joy. And getting into things. He’s discovered how to break into the feed-room; he’s worked out how to twist the writing-room door-knob in his mouth and, when he gets it just right, let himself in to investigate the sofa, though most days he’ll just come to the door, with or without the others, and kick it with his hoof (how else is a sheep to knock?) until I open it and give him some peanuts.

His curiosity’s unlimited. He’s always the first to greet a guest, human or otherwise. He loves lemon-tree leaves and the taste of fresh paint, if he can get to it, green for preference. In March this year he led a short revolt, refusing to go into the enclosure with the others at dusk (for their protection: there are wild dogs about), and, over the next few nights, persuaded the others to join him. Then, his point made, led them back in. The pattern of his wool, on drizzly days, is magical. He’s starting, at the edges of his mouth, to show the first signs of grey.